Stop Throwing a Single Agent at Complex Problems

Jan 17, 2026 · Ensue team

A single agent, even equipped with a frontier AI model, struggles to solve a Putnam math competition problem alone. Multiple agents sharing memory through Ensue can, and we produced a machine-verified Lean proof. GitHub.

Often, the bottleneck in solving complex tasks with AI is assumed to be the model's intelligence.

In this post, we demonstrate how a multi-agent system solves a complex math problem that a single agent using a frontier model struggles with.

Math proofs, like most complex problems, consist of many small, logical steps. Finding a clean composition of dozens, hundreds, or millions of steps is daunting for a single model. Despite rapid improvements in models, they still can't handle prompts that require long, unfamiliar reasoning chains, at least not in one shot.

With Opus 4.5, we observed failures under composition pressure: missed lemmas, inconsistent assumptions, tactic drift, forgotten subgoals, and our favorite, the "it almost compiles" error-fixing death spiral.

Give multiple agents shared memory, and they can solve what one agent struggles with. We use a Putnam 2025 problem to demonstrate this pattern, which can be extended to any complex task: full-application creation, monolith-to-microservices code base restructure, and long-running analysis.

Coordination matters, even with a frontier model

Traditionally, there are two approaches to hard math: manual work that takes years of expertise, or prompting a model. General frontier models are improving, but they are still unreliable for stable end-to-end execution.

So we tried a third path: Solving with an autonomous agent swarm.

We scoped the model's focus to proposing proof tactics for a single step based on "intuition" and facts from previous attempts. We treated proving as a greedy process, reducible to clean, independent subproofs.

The idea: construct a worktree of proofs until the leaves are solvable.

Problems shaped like this make parallelism and concurrency powerful primitives. This is also where shared memory comes in.

Target: Putnam 2025 A2 Math Problem

We picked a concrete problem from the 2025 Putnam math competition - past Claude Opus 4.5's training cutoff to avoid a raw inference solution.

The task: Putnam 2025-A2. Find bounds through Lean formalization where:

noncomputable abbrev putnam_2025_a2_solution : ℝ × ℝ := sorry

-- (1 / π, 4 / π ^ 2)

theorem putnam_2025_a2 (a b : ℝ) :

((a, b) = putnam_2025_a2_solution) ↔

(IsGreatest {a' : ℝ | ∀ x ∈ Set.Icc 0 π, a' * x * (π - x) ≤ sin x} a ∧

IsLeast {b' : ℝ | ∀ x ∈ Set.Icc 0 π, sin x ≤ b' * x * (π - x)} b) :=

sorryOpus 4.5 wasn't able to one-shot or easily solve the math problem. Even with five rounds of follow-up prompting, manually compiling, pasting errors, and guiding it step by step, it never completed a fully valid proof.

The multi-agent architecture: agents plus a memory network

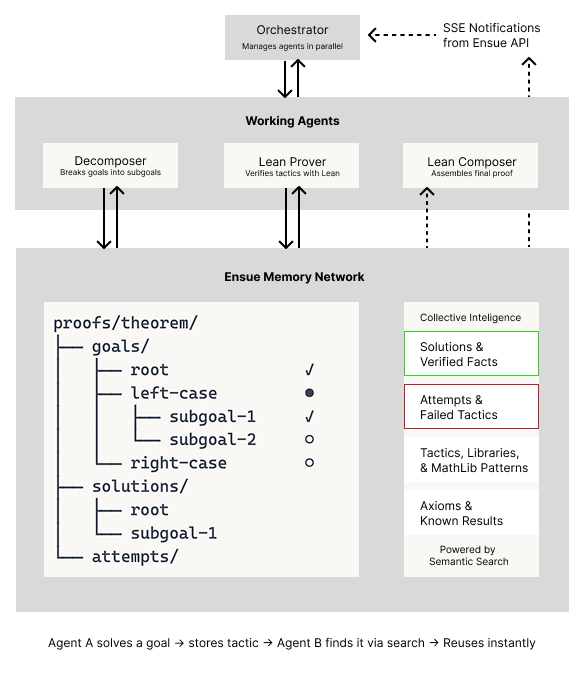

We ran a multi-agent setup with clear roles:

- Orchestrator agent: notified for work and spawns agents as needed.

- Decomposer agents: turn the top-level theorem into a tree of subgoals.

- Prover agents: take a subgoal and verify proof attempts with the Lean compiler, such as tactics, lemmas, imports. Valid theorems are added to collective intelligence for future Provers. (Lean is a theorem prover that makes proofs machine-checkable)

- Memory network (Ensue): stores every artifact

- Subgoals (text + Lean statement)

- Partial and complete proofs

- Work state and claims/locks

- Useful tactics and lemmas discovered

- Preloaded tactics from Mathlib

- Failed decomposition strategies

- Composer agent: assembles the final proof once all goals are decomposed or verified from the work tree. It checks for completeness, verifies syntax, and outputs the final solution

All agents automatically sync state through Ensue, subscribe to memories that other agents create or update, and use Ensue's "search" tool to find relevant context and continue to build on it.

Shared state table stakes for multi-agent collaborations

We found that agents collaborating on complex problems require shared state, and the most effective way to do this was to give them a common memory space.

Here is a concrete example of the runtime interaction with the memory network:

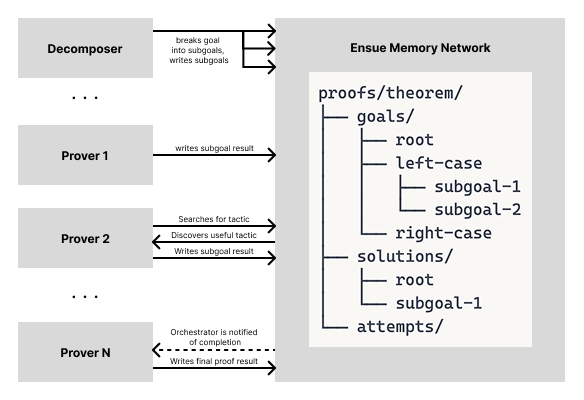

- The Decomposer breaks the complex goal into subgoal 1 and subgoal 2, and stores them on Ensue.

- Prover 1 writes subgoal 1's result to Ensue.

- Prover 2 searches for a tactic memory space, and finds the useful tactic from subgoal 1 that it can apply to subgoal 2.

- Prover 2 writes subgoal 2's results to Ensue.

- Prover 3 reads the results from Prover 1 and 2, and combines their tactics to solve their subgoal.

This is shared state: a common memory that all agents read and write, building on each other's discoveries as they work.

Agentic Loop based on reactive coordination

We also saw how reactive coordination led to more efficient collaboration between agents.

The Orchestrator subscribes to state changes in Ensue. When goals are created, claimed/locked, updated, or fail, it reacts and spawns the right agent.

Example sequence:

- Decomposer writes to Ensue: "Subgoal: prove sin(x) ≥ a·x(π-x) for x in (0,π)"

- Orchestrator sees new subgoal

- Spawns Prover A to work on it

- Subscribes to this subgoal for updates

- Prover A works, fails to complete the subgoal

- Writes a sorry to Ensue

- Orchestrator gets notified of the failure

- Orchestrator spawns a Decomposer

- Decomposer breaks the subgoal into smaller pieces, writes them to Ensue

- Orchestrator sees new subgoals, spawns Prover B and C to work on them

- Orchestrator subscribes to subgoals for updates

- Prover B completes, writes valid tactic to Ensue

- Future Provers can find and reuse this tactic

Reactive coordination helps agent workflows in multiple ways:

First, they don't wait for orchestration. They respond to state changes through Ensue as they happen. The orchestrator spawns and subscribes, but doesn't route every message, avoiding a central bottleneck. Unlike traditional approaches, where provers only talk to an orchestrator, here they can discover each other's work automatically and share tactics through collective intelligence.

Secondly, subscribing to events and acting autonomously on them is much more efficient than traditional approaches, where agents parse logs or poll files, burning tokens on irrelevant context.

Semantic access for context bloat

Context bloat is one of the common problems we observed with complex or long-running tasks. As context and memory grew over time, it became harder for agents to find the right piece of information for their task.

As the proof tree grew, there were dozens of:

- Partial proofs

- Failed, but useful attempts

- Tactics and techniques

- Lemmas at various stages

Without semantic search, agents would:

- Need to know exact key names,

- Read everything (context window explodes), or

- Miss relevant prior work.

With semantic search:

- Provers ask: "What techniques have we used for bounding trigonometric functions?"

- Ensue returns relevant tactics, even if stored under different names

- Agents discover insight from a different branch of the proof tree

Ensue's semantic access over the memories enables agents to efficiently find relevant context by meaning.

The memory network becomes an embedded library of proofs and builds collective intelligence for the agent swarm, searchable with natural language, saving tokens.

Result: Multiple agents coordinating over shared memory solved the complex problem

Agents constructed the proof by collaborating on Ensue until the final proof was compiled successfully. The run took just over 800k Opus 4.5 tokens. We learned that increasing the token allocation also increases subgoal decomposition depth.

The full solution - the Lean formalization and two axioms - can be inspected here. We focused on making this solution accessible by keeping the token usage manageable, so the valid final proof isn't a complete decomposition. Math-specific LLMs, like Aristotle, can solve the outstanding axiom sub-goals easily, and we will include Aristotle-powered agents in future examples. What we're proving is that dozens of Aristotles, working together, can solve hard math problems far outside the frontier model's capabilities alone.

If we had used a single agent, the agent might discover a useful lemma, use it once, forget it, and rediscover it later again with different assumptions. With multiple agents that coordinate over shared memory, that discovery becomes a primitive that the whole system can reuse. This way, the system improves over time without rebuilding context.

Hard problems and efficient multi-agent collaborations require shared memory. The above points are also reasons why simply adding more agents often does not solve a problem. Without shared state and semantic search, you get a noisy room instead of a harmonious collective intelligence.

What's next: Stop Throwing One AI Agent at Hard Problems

The Putnam proof was our test case; a problem with clear success criteria - it compiles, or it doesn't. But the same primitives apply wherever agents need to share discoveries.

Great examples include the OpenAI team building a complete Sora Android application with just a small team and a set of Codex agents, and a complete browser made using billions of tokens flowing across multi-agent workflows by the Cursor team. Cursor independently found a similar structure that worked well for their work on the browser decomposition, which used a tree of work to plan, similar to how we composed a tree of proofs.

One Agent Thinks. Many Agents Compound.

Guided walkthrough

Join our community

The multi-agent Lean proving plugin is open source on GitHub — try it out and generate your own formal proofs, or extend it to solve your own workloads single agents struggle with.

Agents collaborating over a memory network is a new paradigm. We're happy to think along with you about how shared memory can make your agents work better and how to implement it.

Join our Discord or follow us on X for more examples, showcases, and to discuss all things agent coordination. You can start to write to the Ensue shared memory layer today using our Claude Code and Codex Skills.